August 2017

Central banks sale of the century creates bond buying opportunity

By Danica Hampton

The United States Federal Reserve is on track to start reducing the size of its balance sheet in September. It’s a process known as tapering, and although it will kick-off in the US, we are heading into uncharted waters, because it’s likely to occur on a global scale.

Deciding the impact of tapering is important, as it has the potential to disrupt markets, or cause run-away inflation. That’s not a Citi expectation, but it’s a chance to review how we arrived at tapering, and what’s likely to result post-September.

There would be no need for tapering if we had not just gone through a massive cycle of government sponsored asset purchases. In the US alone the size of the Fed’s balance sheet grew from just over $US1 trillion dollars in 2008 when the global financial crisis started, to over $US4 trillion currently. To give that scale between 2007 and 2015 the Fed’s balance sheet went from representing 6% of GDP to 25%, while the European Central Bank (ECB) balance sheet went from 13% of GDP in 2007 to 38% currently.

The central banks grew balance sheet size through quantitative easing (QE), or to put it more simply they created new electronic cash and bought assets from banks. QE was introduced because central banks had run out of room to stimulate economic growth by lowering interest rates. Even pushing rates into negative territory in Europe and Japan had limited impact.

QE was the new lever central banks seized upon to drive economic growth. Essentially the central banks started buying government bonds from banks, although that later expanded into other assets like corporate bonds, and in the case of the Fed, mortgage backed securities.

The aim was simple, to free up bank balance sheets so they could focus on lending to businesses and stimulate the economy, and it worked. Numerous commentators believe it has caused other issues, and there is no doubt tapering has to be handled gently so as not to upset or unbalance markets.

But the key assumption of doomsayers, that it will cause a tsunami of inflation and interest rates increases once asset sales start, is not a Citi view.

While there is no post-GFC world to draw references from, tapering is not new, and there are numerous examples of central banks reducing balance sheet since 2006. The overriding conclusion to be drawn from examining these incidents is that markets act unpredictably.

And that suggests it was a range of activities occurring at the time of tapering that was driving markets.

On the global economic front we are experiencing a return to trend economic growth, lower for longer interest rates, inflation and wage growth, and relatively benign conditions as volatility subsides from the roller-coaster of the past decade.

Citi analysis suggests for every 1% GDP reduction in the Fed’s balance sheet - which is roughly $US190 billion or what is expected in the first year of US tapering – the yield on 10-year US treasuries will increase six basis points.

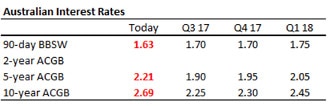

For the next couple of years you can see Citi’s forecasts in the table below, which also incorporates Australia.

Take your next step with Citigold

The US tapering is likely to coincide with similar moves from the ECB, Bank of England, and the Swedish central bank Rikbank. The result will be tightening financial conditions, as private capital soaks up government asset sales. But we expect it will be a measured sell-down, and adjusted as necessary so as to not disrupt markets unduly.

While tapering is a global story, there are domestic issues that will impact local rates. With the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) expected to keep the cash rate steady, and little domestic price/wage pressure, it’s a low fuel environment for Australian interest rates. As such, we expect Australian 10-year yields to fall in line with the expected declines in US treasury yields.

Combine that with contained inflation and the 10-year part of the Australian corporate bond curve looks attractive. A decline in 10-year US treasury yields will result in a broad based fall in corporate bonds yields of a similar tenor – leading to higher bond prices and a positive return for investors.

We see value in the 5-10 year section of the corporate bond curve, and expect the RBA’s neutral stance will help Australian rates outperform those in a US rising rate environment. We view the recent weakness in bond prices, caused by an overdone reaction to perceived dovishness from key central banks, as a bargain hunting opportunity.

Any advice is general advice only. It was prepared without taking into account your objectives, financial situation, or needs. You should consider if this advice is appropriate for your situation. We recommend you read the Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) or Terms and Conditions, available online or via a Citibank branch, in addition to seeking independent legal, financial and taxation advice on your personal circumstances before acting on the information contained in this material.

This material is for general information only. All opinions are subject to change without notice. This material is taken from sources which are believed to be accurate; however Citibank accepts no liability of any kind to any person who relies on the information in it. Investments are not deposits or other obligations of, guaranteed, or insured by Citibank N.A., Citigroup Inc., or any of their affiliates or subsidiaries, or by any local government or insurance agency, and are subject to investment risks, including the possible loss of the principal amount invested. Investments are subject to risk, including loss of income and principal. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance. Due to exchange rate fluctuations, you risk losing capital if you invest in foreign currency. Some products are not available to US persons and may not be available in all jurisdictions.